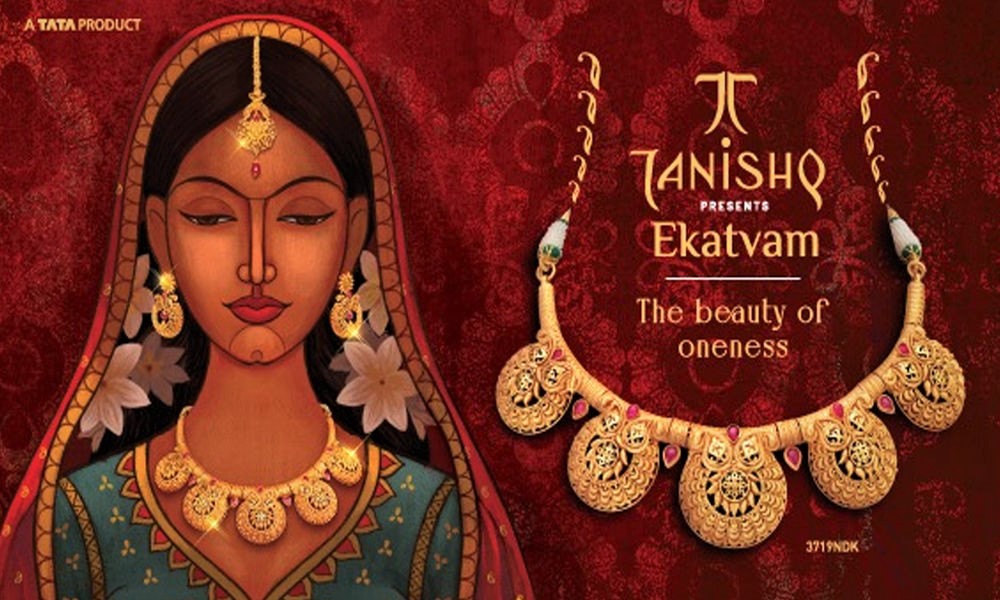

Voltaire once said that ‘those who can make you believe absurdities can also make you commit atrocities.’ Unfortunately, in this post-truth era in India, absurdities are becoming the dominant narrative, people no longer seem to care what is true and are happy to be influenced by prejudices and driven by emotions and not by facts[1]. At the start of this year’s autumnal festive period Tanishq, the famous Indian jewellery brand created an advertisement. This 45-second advertisement titled “Ekatvam (Oneness)” featured a Muslim family celebrating a traditional South Indian baby shower ceremony for their pregnant Hindu daughter-in-law. The advertisement, amid allegations of promoting “love jihad”[2] and intense trolling along with calls for a boycott on social media, was later withdrawn. Bollywood actor Kangana Ranaut claimed that it glorified “love jihad and sexism”, a total rejection of contrary evidence. She tweeted that:

‘as Hindus we need to be absolutely conscious of what these creative terrorists are injecting in to our subconscious, we must scrutinise, debate and evaluate what is the outcome of any perception that is fed to us, this is the only way to save our civilisation #tanishq’[3]

The advertisement was viciously trolled[4], with some Twitter users creating the hashtag #BoycottTanishq[5]. It would not be simplistic to focus solely in terms of the rise of Hindu nationalism fuelled by a rapid intensification of majoritarian aggression[6]. The ad was politicised by religion-focused rhetoric and cultural chauvinism, which contradicts Indian constitutional secularism. In recent years we have seen a significant increase in right-wing online vigilantism (digilantism). However, most notably this incident again highlights increasing instances of intolerance promoted by the divisive elements of social media based on a deep-rooted communal hatred that is multiplied exponentially because of the dominance of “echo-chamber”[7] communication on Twitter[8] that has challenged secularism and promoted an environment of “cultural policing”[9]. Social media has been a driving force behind religion-oriented political polarisation in India[10]. Titan’s (the parent company) stocks fell sharply because of the controversy.[11] After withdrawing the ad, Tanishq said in a statement:

‘the idea behind the Ekavatam campaign is to celebrate the coming together of people from different walks of life, local communities and families during these challenging times and celebrate the beauty of oneness. This film has stimulated divergent and severe reactions, contrary to its very objective’.

Although in India there is no legal restraint on “thought”, only legal restraints on communications but a dispassionate analysis of the advertisement will prove it had no “deliberate and malicious” intent to insult religious sentiments or used language that “creates enmity and hatred among the citizens or denigrates religious beliefs.” So, why is it that, even when reported extensively, there have drawn limited condemnation from the vast majority of India’s literate population? Unfortunately, in recent times we have seen that opinions or expressions that do not follow the politico-ideological beliefs of “Hindutva” are severely criticised by Hindu nationalists, who often target individuals[12]. The ideological narrative has been confined to the exclusion of minorities and homogeneity of a narrow and rigid version of Hinduism. ‘Hindu syncretism, eroticism, dissent, and secular practice are constructed rhetorically as “foreign”[13] imports, while at the same time providing a cover for Hindutva to claim tolerance as its abiding virtue in venues where the rhetoric of diversity proves profitable’[14]. Even academics in India tend to tiptoe around contentious topics, fearing repercussions. This fear is no mere hyperbole[15]. Individuals like Bollywood actor Kangana Ranaut defended their hatemongering against Tanishq by arguing that those who hurt Hindu sentiments or threaten Hindu beliefs are not acceptable.

Ad industry watchdog Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) said its panel had reviewed the Tanishq advertisement after receiving a complaint of it being objectionable and found unanimously

‘…that nothing in the advertisement was indecent or vulgar or repulsive, which is likely in the light of generally prevailing standards of decency and propriety, to cause grave and widespread offence.’[16]

“Love Jihad” is a term for an Islamophobic conspiracy theory that alleges that Muslim men target women belonging to non-Muslim communities to convert them to Islam by feigning love and marrying them[17]. The popularity of the term in India has become synonymous with the rise of right-wing identity politics. However in February this year, the Indian government told the parliament that the term “love jihad” is not defined under existing laws and no case has ever been reported by any central law enforcement agency, thereby officially distancing itself from the term used by right-wing fundamentalist groups referring to several cases of inter-faith marriages[18].

In India, varied interests must monitor government, given the intricate, plural, and even contradictory aspirations of a socially divided, hierarchical society. However, some the institutions that are supposed to ensure scrutiny seem to have either lost their functional independence[19], or it may be that Hindu nationalist ideology has permeated the state apparatus and formal institutions[20]. Incidentally, the Chairperson of the National Commission for Women (NCW) has been widely criticised for discussing the “rise in love jihad cases” with the Governor of Maharashtra thereby providing incentives for the conspiracy theorists and raising questions about her suitability to hold the position of such significance which demands absolute impartiality[21]. This propagating of extreme religious nationalism suggests religious-nationalist groups’ desire in encroaching upon government power. Thus, the enforcement of certain ideologies by religious-nationalist groups manifest their open desire in power-sharing and taking control over the lives of people in a non-democratic manner. This progress is undoubtedly a challenge for a society based on secular-liberal democratic values.

‘The communalisation of politics in India is a product of the democratic system which is prone to cycles of degenerative politics where normative content and ideological conviction are sacrificed for survival in political office’.[22]

The Tanishq advertisement controversy also highlights another chilling realisation, the attempt to restrict freedom of expression in India. We have seen that due in large part to heightened political sensitivity and a culture of appeasement, the meaning as well as the scope of freedom of expression, which is protected under the Constitution of India, (Article 19) have been tested in recent times.[23] The right to freedom of speech and expression is highly qualified, subject to what the government deems “reasonable” restrictions[24]. However, the prohibition of expression on the grounds of “offensiveness”[25] would produce undesirable consequences for liberal democracies.[26] I further argue that the “freedom to be creative and to criticise” should be protected to ensure that the diverse opinions are sincerely held within society[27]. There is no right “not to be offended” from an expression. Instead, this case highlights a culture of intolerance among the paranoid Hindu nationalists towards creativity[28] as they fail to distinguish between forms of creativity that do and those that do not threaten public order, decency, or morality. In the world’s largest democracy, people are losing their right to express an opinion because of fear of mob persecution. Interestingly, in India, secularism is frowned upon by both radical Muslims[29] and Hindu nationalists. ‘Anti-secularist arguments are embedded in the generic critique of modernity where secularism is associated with the project of modernity, science, and rationality as it mocks the believer for his morality and religiosity‘[30].

The problem in India is not that the constitution does not guarantee free speech, but that it is easy to silence free speech because of a combination of specific laws[31], an inefficient criminal justice system, and a lack of jurisprudential consistency. India’s legal system is infamous for being clogged and overwhelmed, leading to lengthy and expensive delays; it can discourage even the innocent from fighting for their right to free speech. India’s hate speech laws are so broad in scope that they infringe on peaceful speech and fail to meet international standards[32]. Instead, to protect minorities and the powerless, these laws are often used at the behest of influential individuals or groups, who claim that they have been offended, to silence speech they do not like. The State too often pursues such complaints, thereby leaving members of minority groups, writers, artists, and scholars facing threats of violence and legal action[33].

India is a mosaic of many overlapping cultures and religions. For decades after independence, Indianness celebrated the country’s pluralism. The rise of ethnic nationalism brought a “sense of cultural superiority” that it has been argued to have been developed from a sense of grievance against alleged injustices done to Hindus as a group due to a culture of appeasement politics that had dominated Indian politics for decades. However, India is supposed to be an inclusive nation—not a fundamentalist nation, and certainly not a theocracy. Why is India looking inward in this manner now? Why must Indians regress to the level of unequal societies? The underlying problem for creative expression in India today is not merely religious intolerance, but weak institutions that are incapable of upholding liberal values. If religious extremism continues to grow, it will drag India’s democracy down with it. Finally, while freedom of expression is primarily negative in nature, in as much as it constrains the State’s ability to limit expression, it also has an essential positive dimension. One cannot choose to be tolerant along partisan lines[34]. In this aspect, the right requires the State to take positive action to protect it. In my view, the Government of India should take proactive steps to discourage the spread of hegemonic narrative.

Acknowledgement

I want to thank Prof Ian Cram, School of Law, University of Leeds, for his encouraging comments.

[1] Mercier, H. (2020). Not born yesterday: The science of who we trust and what we believe. Princeton University Press

[2] Gupta, C. (2009). Hindu Women, Muslim Men: Love Jihad and Conversions. Economic and Political Weekly, 44(51), 13-15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25663907

[3] https://twitter.com/KanganaTeam/status/1315688976414433280

[4] Not just against this particular ad “trolling” in general is used to silence dissenting voices. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/03/online-hate-campaign-targets-indian-streaming-stars

[5]https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-tanishq-ad-withdrawn-amid-trolling-boycott-calls/362106

[6] Chatterjee, S. (2019). Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism is Changing India: Angana P. Chatterji, Thomas Blom Hansen and Christophe Jaffrelot (eds). Hurst and Company, London, 2019. pp. xii+ 537

[7] Echo chambers are a process of self-selection that confines communication to ideologically aligned cliques. See Del Vicario M, Bessi A, Zollo F, Petroni F, Scala A, Caldarelli G, et al. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences;113(3):554–559.

[8]The growing importance in understanding rumour spreads has spurred research into analysing rumour propagation patterns on social media.

[9] Jaffrelot, C. (2017). India’s Democracy at 70: Toward a Hindu State? Journal of Democracy; 28 (3) 50 https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0044

[10]https://www.firstpost.com/india/how-facebooks-structure-as-data-gathering-behaviour-manipulating-communication-conduit-stokes-its-right-wing-bias-8774891.html

[11]https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/after-boycotttanishq-trend-shashi-tharoor-asks-why-dont-they-boycott-india-2309248

[12] In India, it is the right-wing that could spend money on massive Facebook advertising and Facebook, with its ownership of Instagram and WhatsApp, controls much of digital communication in India. Facebook is being criticised for partisan regulation of political content in India. https://www.article-14.com/post/inside-facebook-s-bjp-bond-key-tie-ups-with-modi-govt-its-special-interests

[13] Swara Bhasker, a Bollywood actor was inundated with thousands of tweets and threats, of being anti-Indian and anti-Hindu for her role in the Amazon Prime series “Rasbhari”.

[14] Banaji, S (2018). Vigilante Publics: Orientalism, Modernity and Hindutva Fascism in India, Javnost – The Public, 25:4, 333-350

[15]Tanishq pulls ad featuring inter-faith match, a sign of the angry, fearful times in which we live. See Tripathi, S. (2015). Fear of Mob. In Imposing Silence, The Use of India’s Laws to Suppress Free Speech. A Joint Research Project by the International Human Rights Program (IHRP) at the University of Toronto, and PEN Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto

[16]https://www.livemint.com/industry/advertising/advertising-associations-come-out-in-support-of-tanishq-over-withdrawn-campaign-11602674294763.html

[17] Gupta, C. (2016). Allegories of ‘Love Jihad’ and Ghar Vapasi: Interlocking the Socio-Religious with the Political. Journal of African and Asian Studies, 84:2, 291-316

[18]https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/feb/05/love-jihad-not-defined-under-existing-laws-no-case-reported-yet-government-in-parliament-2099277.html

[19] See Chatterjee, S. (2019). Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism is Changing India: Angana P. Chatterji, Thomas Blom Hansen and Christophe Jaffrelot (eds). Hurst and Company, London, 2019. pp. xii+ 537. The authors of the book, “Majoritarian State” argues how Hindutva activists exert control over civil society via vigilante groups, cultural policing and violence. As this majoritarian ideology pervades the media and public discourse, it also affects the judiciary, universities and cultural institutions, increasingly captured by Hindu nationalists.

[20]https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/20/hindu-supremacists-nationalism-tearing-india-apart-modi-bjp-rss-jnu-attacks

[21] A petition was filed before the Bombay High Court seeking a direction to remove Rekha Sharma, the Chairperson of the National Commission for Women (NCW), over her tweet on ‘love jihad’. The petitioner argues that there has been a violation of Articles 14 (equality before law), 21 (protection of life and personal liberty) and 25 (all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience and the right to profess, practise freely, and propagate religion subject to public order, morality and health) of the Indian Constitution. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/plea-against-ncw-chairperson-over-love-jihad-tweet/article32967524.ece

[22] Kothari, R (1998). Communalism in Indian Politics, Rainbow Publishers, 15

[23] India ranked 142 out of 180 countries in the Reporters without Borders Press Freedom Index

[24] The state can silence its citizens for any number of reasons, including “public order,” “decency or morality” and “friendly relations with foreign states”, but these restrictions are subject to the test of reasonableness. (First Amendment to the Constitution of India was made due to the Supreme Court’s verdict in ‘Crossroads v State of Madras’ (1950)). There is an argument that these restrictions appear “to take away the very soul out of the protective clauses”. It cuts the very root of fundamental rights and the fundamental rights cease to be fundamental.

[25] Cram, I. (2009). The Danish Cartoons, Offensive Expression and Democratic Legitimacy’, in Hare, I., and Weinstein, (eds), Extreme Speech and Democracy, OUP, 322, 311-330

[26] Cram, I., (2006). Contested Words: Legal Restrictions on Freedom of Speech in Liberal Democracies, Ashgate, 140

[27] In 1989, the Supreme Court of India held that “the State cannot prevent open discussion and open expression, however hateful to its policies”, Rangarajan vs P. Jagjivan Ram (1989)

[28] A Member of Legislative Assembly in Maharashtra has approached the police seeking action against megastar Amitabh Bachchan and the makers of TV show ‘Kaun Banega Crorepati 12’ for allegedly hurting Hindu sentiments. https://www.firstpost.com/entertainment/bjp-mla-seeks-police-action-against-amitabh-bachchan-over-kaun-banega-crorepati-question-8978651.html

[29] Nusrat Jahan, a Member of Parliament has received death threats on social media for dressing up as Goddess Durga for advertisements for a clothing line that she posted on Instagram on 17 September. Within hours of Ms Jahan posting a video and photos of her photoshoot for the ad, in which she is dressed as the goddess and holding a Trishul (trident), threats started popping up on her timeline, from India and Bangladesh. This is not the first time Ms Jahan has been threatened and abused for her views or stand on issues. She was abused for marrying a Hindu, wearing “sindoor” or vermillion and participating in Rath yatra soon after. Photos of her at Durga Puja pandals last year with her husband had gone viral and drawn abuse.

[30] Singh, A (2018). Conflict between Freedom of Expression and Religion in India—A Case Study, Soc. Sci. 7(7), 108

[31] There are several sections in the Indian Penal Code that are widely used and abused to ban works of art, films, and books. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/05/24/stifling-dissent/criminalization-peaceful-expression-india

[32] The Indian government is evidently concerned about the reach of the platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime, as these platforms perhaps unwittingly have become a space for dissent and critique.

[33] Basu. S. (2019) WhatsApp, India’s Favourite Chat App: A Threat To Democracy?” Risk Group

[34]The arrest of one of India’s most polarising television journalists Republic TV’s Arnab Goswami drew sharp criticism and condemnation from ministers in the government, right-wing political leaders and supporters. However, many have accused the ruling party of hypocrisy, pointing out that many journalists and publications that publish pieces critical of the Federal government are regularly named as “anti-nationals” and arrested or charged under criminal law. During the Covid-19 crisis, more than 50 journalists have been detained for critical coverage.

Implications of Quantum Cybersecurity

Implications of Quantum Cybersecurity